BREAKING NEWS : GH Just Made Its Biggest Villain Part of a Bigger Machine

General Hospital has spent decades perfecting the art of the singular villain: the schemer with a vendetta, the criminal mastermind driven by obsession,

the tyrant whose downfall arrives in a blaze of exposure and arrest. But with one quiet, chilling reveal, the soap has fundamentally rewritten its own rules.

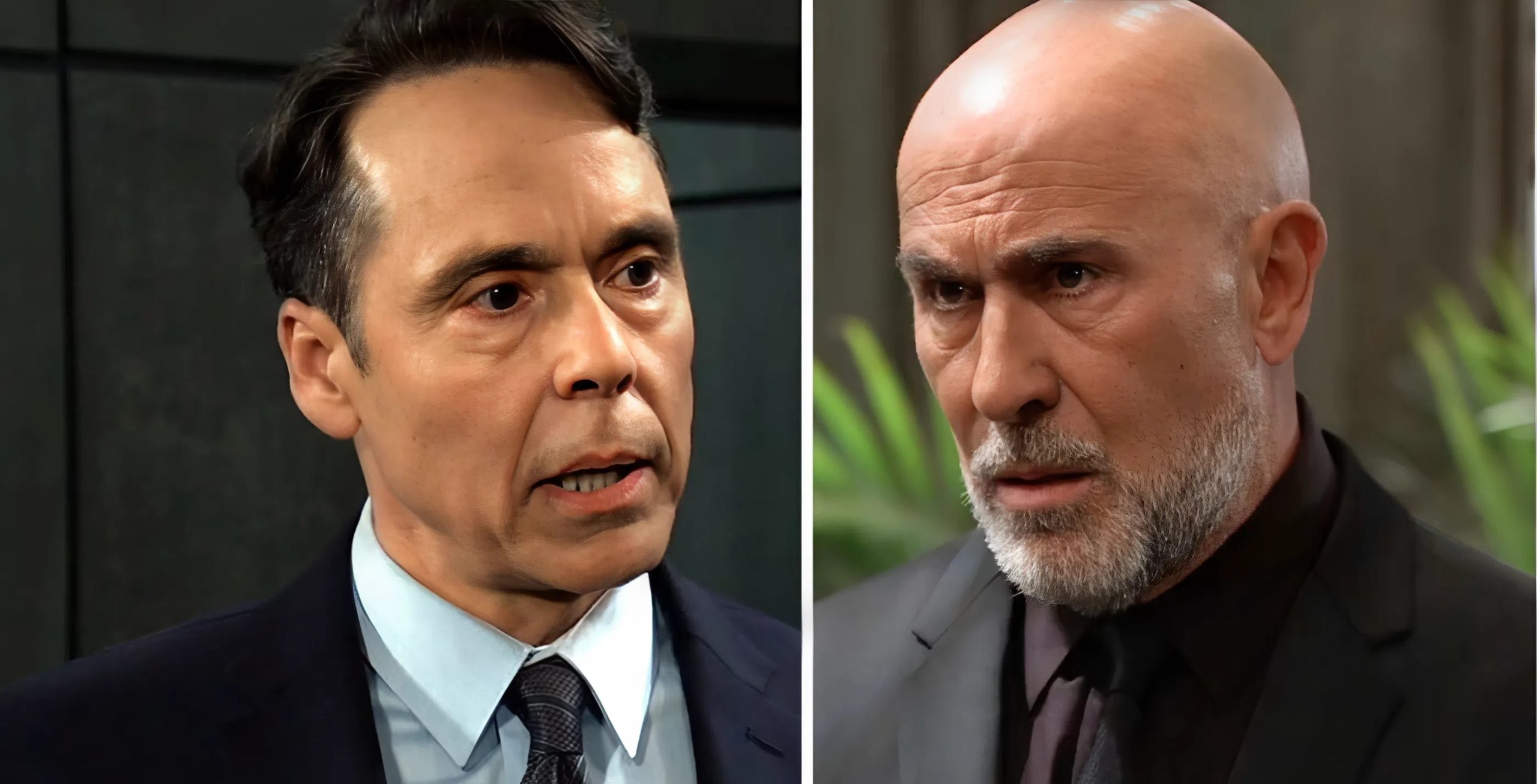

By confirming Ross Cullum as Sidwell’s boss — and the true authority looming over Jack, the WSB, and more — GH hasn’t simply introduced a new antagonist.

It has exposed a system. And systems are far harder to destroy.

From the moment Ross Cullum stepped onscreen, the temperature in Port Charles changed. He didn’t storm into scenes with bluster or theatrics. He didn’t posture, threaten, or revel in cruelty. Instead, he arrived already in control. The show made its point with surgical precision: Sidwell answers to him. Jack answers to him. And when Cullum coolly identified Anna Devane as a “problem” that needed handling, the message landed with brutal clarity. This was no longer about rival power players clashing. This was about an institution deciding who gets to exist.

The implications of that shift are enormous. For years, Sidwell had been framed as a top-tier threat — dangerous, calculating, convinced he was the smartest man in every room. Watching him argue upward shattered that illusion. When Cullum shut him down, Sidwell didn’t push back. He didn’t escalate. He complied. In that instant, Sidwell transformed from mastermind to middle management.

And that reframing is far more unsettling than simply topping him with a louder, more violent villain.

Sidwell was never incompetent. He remains ruthless, capable, and lethal. But General Hospital has revealed him to be expendable. A cog. A highly placed one, perhaps, but a replaceable part of something much larger. The earlier hints now snap into focus — the references to a mysterious “him,” the unseen authority pulling strings from above. The show didn’t retcon Sidwell’s past. It recontextualized it.

That choice matters. You can defeat a lone villain. You can expose them, arrest them, or kill them. But you can’t dismantle a machine by removing one operator. When a threat becomes institutional, bleeding on the floor doesn’t scare it. It merely proves you’re inconvenient.

Ross Cullum changes the shape of danger in Port Charles precisely because he doesn’t need to make threats. His authority does the work for him. When he dismisses Anna as a distraction, there’s no personal animosity in his tone — and that’s what makes it terrifying. Anna isn’t a rival. She isn’t an enemy worthy of obsession. She’s a variable. A loose end.

For a character like Anna Devane, who has survived decades of espionage, betrayal, and moral compromise, this is perhaps the most dangerous position she’s ever been in. She’s no longer battling someone who wants revenge or domination. She’s facing an organization that wants efficiency. And efficiency doesn’t argue. It erases.

Andrew Hawkes plays Cullum with a restraint that radiates confidence rather than mystery. This isn’t a man who needs to explain himself. He’s accustomed to rooms going quiet when he speaks. His power is clean, bureaucratic, and absolute. He doesn’t rush because time works for him. He doesn’t justify his decisions because he doesn’t expect resistance.

That performance choice is what makes the reveal land so effectively. Cullum isn’t a shadowy figure cloaked in intrigue. He’s a professional. And professionals don’t monologue — they delegate.

With Cullum in place, Sidwell’s role becomes clearer. He isn’t the story anymore. He’s evidence. Proof that the corruption in Port Charles runs higher, quieter, and far more efficiently than anyone realized. The real threat isn’t louder violence or bigger explosions. It’s the cold normalization of wrongdoing wrapped in official authority.

Jack answering to Cullum redraws the entire power map. What once looked like tangled loyalties now reads as a hierarchy. Every decision, every betrayal, every “rogue” action suddenly feels sanctioned. That revelation forces viewers to reconsider past events. How many crimes weren’t deviations, but directives? How much chaos was actually policy?

For the citizens of Port Charles, this shift is catastrophic. When villains act alone, they leave fingerprints. When they act as part of a system, accountability vanishes. Records disappear. Witnesses recant. Investigations stall. People don’t just die — they fade out of the narrative, written off as collateral damage.

The genius of this move is that the danger hasn’t technically increased. No new weapons have been introduced. No armies have marched in. Instead, the threat has become organized. And that’s when fear changes form. It stops being explosive and starts being suffocating.

For Anna, the stakes couldn’t be higher. She’s spent her life navigating gray areas, believing that truth and persistence would eventually prevail. But institutions don’t fear truth. They bury it. And when Cullum decides someone is a liability, there’s no courtroom drama, no heroic last stand. There’s just removal.

For the audience, the reveal is both clarifying and chilling. General Hospital isn’t asking viewers to fear a single villain anymore. It’s asking them to fear the absence of one. The idea that if Sidwell falls, nothing improves — because someone else will simply step into his place.

This is a bold evolution for the show’s storytelling. By making its biggest villain part of a larger machine, GH has raised the narrative stakes without resorting to spectacle. It has turned power itself into the antagonist.

And once power becomes faceless, unaccountable, and efficient, survival in Port Charles stops being about winning.